Reprinted with permission

from the Rutland Herald / Barre-Montpelier Times Argus,

Feb. 6, 2011

The 17-year-old Vermont high school junior, hoping to put a face on the

state's population of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender youth, eagerly

agreed to this paper's request to publish his name, profile and photo on the

front page.

"It's a really awesome opportunity," he said.

So why am I masking him here as "Hart" (not his real name) and generalizing

the specifics of a coming-of-age story understood by an estimated 10 percent

of society?

Vermont has advanced as a leader in equality legislation throughout Hart's

life. The state adopted an anti-discrimination law just before his birth in

1993, then became the first to approve same-sex unions in 2000 before adding

full marriage rights in 2009.

But that doesn't mean everyone supports Hart and his peers. Read, listen or

log onto any national news outlet the past several months and you'd learn

about a rash of bullying, harassment and suicides involving teenagers facing

questions about their sexuality.

Vermont isn't immune to the problem. One-third of the state's gay and

lesbian students say they've been bullied, according to the most recent

Youth Risk Behavior Survey of nearly all eighth- through 12th-graders - more

than double the percentage reported by straight peers. Half of all gay and

lesbian students have found themselves in a physical fight and a quarter

threatened or injured with a weapon at school.

"It's all over the news," Hart says, "but I feel that not enough people care

about this issue, or if they do care, not enough people are doing anything

about it."

The student recalls seventh grade. For a majority of boys, middle school

brings the surprise that girls can morph into magnets. But for Hart,

opposites didn't attract.

"My first realization was when I was 12 - I knew that I was different."

Was it simply a phase? And, if not, what would people say?

"It's just not something that anyone in middle school really talks about or

knows how to talk about. And it was something I didn't want to admit to

myself."

That changed when Hart went to high school. In ninth grade, he met a

boyfriend who supported him when he told his parents. In 10th grade, Hart

joined his school's Gay-Straight Alliance, one of more than 30 such groups

in communities throughout the state.

"Freshman year I wasn't involved - mostly because I had the assumption that

if I joined, everyone would find out."

The feared paparazzi never popped up. Instead, Hart stepped forward himself.

During a nationwide "Ally Week" last fall, he asked classmates to sign a

pledge to "not use anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender language or

slurs" and "intervene, if I safely can, in situations where students are

being harassed."

Hart, who has faced verbal slurs but no physical threats, also is helped by

Outright Vermont. The statewide nonprofit advocacy organization began in

1989 after a national survey reported higher rates of depression and suicide

attempts among gay and lesbian youth that, in turn, can increase school

truancy and alcohol and drug use.

Two decades later, a new generation of problems is making news.

"It's devastating," Outright executive director Melissa Murray says of the

most recent headlines. "Youth are dying, but the recent media attention is

making people pay attention. We've been invited in to so many different

schools that never would have invited us before."

Last fall alone, Outright presented programs to 1,000 students, many in

conservative communities in the state's Northeast Kingdom. According to the

organization's most recent Safe Schools Report Card, nearly half of

Vermont's 61 public high schools now have gay-straight alliances and 57

percent offer a gender-neutral bathroom, with 11 "top ranked" boasting both

of those supports as well as specific anti-harassment programs.

(Log onto www.outrightvt.org for the full list.)

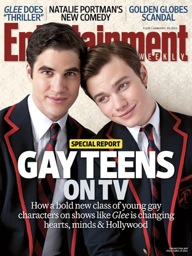

Life seems to be looking up for Hart and his Vermont peers. The man who

championed the state's new same-sex marriage law was just inaugurated as

governor, while Entertainment Weekly dedicated a recent cover to the media's

advancement of gay teens.

"How did gay teens go from marginalized outcasts and goofy sidekicks," the

magazine wrote, "to some of the highest profile - and most beloved -

characters?"

Then again, Hart knows real life doesn't always follow a script. After this

newspaper finished the teenager's profile (headlined "Student hopes to

silence hate by speaking out") but before it took his picture, his parents

expressed mixed feelings about publication.

His mother worried about Hart's security - would taking aim at harassment

instead attract it? - but ultimately decided he was old enough to make his

own decision.

His father voiced similar concerns: What would others think, and how would

they respond? But he spoke less about the possible reaction of his son's

classmates than of the potential static from his own co-workers and

neighbors.

The safest course, he believed, would be to stay silent. And so this paper,

lacking a photo and full family consent, chose not to run the profile.

Hart, bowing to the decision, stopped communicating on his social networking

sites for weeks. Recently, however, he has Twittered peers about a new

boyfriend, written Facebook condolences to the family of the latest

teen-suicide victim, and resumed his Human Rights Campaign e-mails to

politicians in support of marriage and military equity.

"It's definitely not what most teenagers do," he says of his advocacy, "but,

in my opinion, everyone should have equal rights. People make a lot of

assumptions about the LGBT community, when really we're just like everyone

else."

Hart still lacks parental permission to be named or photographed by this

paper. But that hasn't stopped the teenager from speaking out.

"Someone," he reasons, "has to be that person who stands up."

kevin.oconnor@rutlandherald.com

from the Rutland Herald / Barre-Montpelier Times Argus,

Feb. 6, 2011

The 17-year-old Vermont high school junior, hoping to put a face on the

state's population of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender youth, eagerly

agreed to this paper's request to publish his name, profile and photo on the

front page.

"It's a really awesome opportunity," he said.

So why am I masking him here as "Hart" (not his real name) and generalizing

the specifics of a coming-of-age story understood by an estimated 10 percent

of society?

Vermont has advanced as a leader in equality legislation throughout Hart's

life. The state adopted an anti-discrimination law just before his birth in

1993, then became the first to approve same-sex unions in 2000 before adding

full marriage rights in 2009.

But that doesn't mean everyone supports Hart and his peers. Read, listen or

log onto any national news outlet the past several months and you'd learn

about a rash of bullying, harassment and suicides involving teenagers facing

questions about their sexuality.

Vermont isn't immune to the problem. One-third of the state's gay and

lesbian students say they've been bullied, according to the most recent

Youth Risk Behavior Survey of nearly all eighth- through 12th-graders - more

than double the percentage reported by straight peers. Half of all gay and

lesbian students have found themselves in a physical fight and a quarter

threatened or injured with a weapon at school.

"It's all over the news," Hart says, "but I feel that not enough people care

about this issue, or if they do care, not enough people are doing anything

about it."

The student recalls seventh grade. For a majority of boys, middle school

brings the surprise that girls can morph into magnets. But for Hart,

opposites didn't attract.

"My first realization was when I was 12 - I knew that I was different."

Was it simply a phase? And, if not, what would people say?

"It's just not something that anyone in middle school really talks about or

knows how to talk about. And it was something I didn't want to admit to

myself."

That changed when Hart went to high school. In ninth grade, he met a

boyfriend who supported him when he told his parents. In 10th grade, Hart

joined his school's Gay-Straight Alliance, one of more than 30 such groups

in communities throughout the state.

"Freshman year I wasn't involved - mostly because I had the assumption that

if I joined, everyone would find out."

The feared paparazzi never popped up. Instead, Hart stepped forward himself.

During a nationwide "Ally Week" last fall, he asked classmates to sign a

pledge to "not use anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender language or

slurs" and "intervene, if I safely can, in situations where students are

being harassed."

Hart, who has faced verbal slurs but no physical threats, also is helped by

Outright Vermont. The statewide nonprofit advocacy organization began in

1989 after a national survey reported higher rates of depression and suicide

attempts among gay and lesbian youth that, in turn, can increase school

truancy and alcohol and drug use.

Two decades later, a new generation of problems is making news.

"It's devastating," Outright executive director Melissa Murray says of the

most recent headlines. "Youth are dying, but the recent media attention is

making people pay attention. We've been invited in to so many different

schools that never would have invited us before."

Last fall alone, Outright presented programs to 1,000 students, many in

conservative communities in the state's Northeast Kingdom. According to the

organization's most recent Safe Schools Report Card, nearly half of

Vermont's 61 public high schools now have gay-straight alliances and 57

percent offer a gender-neutral bathroom, with 11 "top ranked" boasting both

of those supports as well as specific anti-harassment programs.

(Log onto www.outrightvt.org for the full list.)

Life seems to be looking up for Hart and his Vermont peers. The man who

championed the state's new same-sex marriage law was just inaugurated as

governor, while Entertainment Weekly dedicated a recent cover to the media's

advancement of gay teens.

"How did gay teens go from marginalized outcasts and goofy sidekicks," the

magazine wrote, "to some of the highest profile - and most beloved -

characters?"

Then again, Hart knows real life doesn't always follow a script. After this

newspaper finished the teenager's profile (headlined "Student hopes to

silence hate by speaking out") but before it took his picture, his parents

expressed mixed feelings about publication.

His mother worried about Hart's security - would taking aim at harassment

instead attract it? - but ultimately decided he was old enough to make his

own decision.

His father voiced similar concerns: What would others think, and how would

they respond? But he spoke less about the possible reaction of his son's

classmates than of the potential static from his own co-workers and

neighbors.

The safest course, he believed, would be to stay silent. And so this paper,

lacking a photo and full family consent, chose not to run the profile.

Hart, bowing to the decision, stopped communicating on his social networking

sites for weeks. Recently, however, he has Twittered peers about a new

boyfriend, written Facebook condolences to the family of the latest

teen-suicide victim, and resumed his Human Rights Campaign e-mails to

politicians in support of marriage and military equity.

"It's definitely not what most teenagers do," he says of his advocacy, "but,

in my opinion, everyone should have equal rights. People make a lot of

assumptions about the LGBT community, when really we're just like everyone

else."

Hart still lacks parental permission to be named or photographed by this

paper. But that hasn't stopped the teenager from speaking out.

"Someone," he reasons, "has to be that person who stands up."

kevin.oconnor@rutlandherald.com